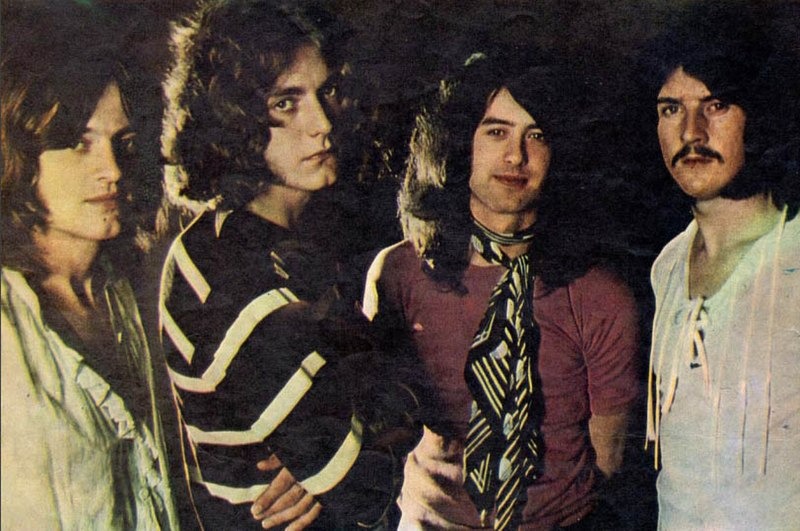

Critics never seemed to give Led Zeppelin much of a break during the heyday of rock excess. Despite producing enormous epics like “Stairway to Heaven,” critics criticized the band’s debut album and said they were bottom-of-the-barrel rock and roll, despite the fans’ cries for the release of the band’s second album. Houses of the Holy marked the beginning of the band’s change in direction as their self-titled period came to an end.

Throughout its duration, Zeppelin avoids becoming too mired in blues traditions, preferring to broaden their musical horizons by including elements of world music and funk. John Paul Jones has never been fond of “D’Yer Ma’ker,” even though songs from this era like “Over the Hills and Far Away” and “The Rain Song” are still standards.

Robert Plant does his hardest to play a reggae-influenced tune, but there’s something tonally odd about the song when compared to every other track on the record. Jones blames John Bonham for the song’s erratic tempo, even though practically every member of the band contributed to this dubious tune. He discusses this in the Led Zeppelin FAQ (via Cheatsheet), “It would have been all right if Bonham had worked at the part. The whole point of reggae is that the drums and the bass really have to be very strict about what they play. And he wouldn’t be, so it sounded dreadful.”

Bonzo’s drumming in this song seems out of place compared to his regular sound. Bonham’s propensity to play slightly behind the beat never worked on this song since reggae music was always locked into a tight pattern. It seems as if the tune is hobbling from one verse to the next without ever settling down. Undoubtedly, Bonham’s influence in Led Zeppelin stemmed from his distinctive behind-the-beat approach. Bonham’s drum parts always gave the album a “feel,” making the song sound like a live creature rather than something that could be learned from sheet music, even if not every drum beat he performed was exactly on the grid.

The whole essence of Zeppelin’s strength lies in that kind of unbalanced counterpoint, with Jimmy Page consistently leading up the midsection of the song as Page performed ahead of the beat. Something like “Black Dog,” where every band member is performing at full capacity in between Plant’s laments, is the ideal illustration of their cooperation executed flawlessly. The project may have failed altogether if another musician had been playing one of those sections.

Even though “D’yer Ma’ker” didn’t succeed, the band was still committed to taking chances and trying new things for the remainder of their career. On Physical Graffiti, every other song talked about broadening their horizons and evolved into epics like “Kashmir.” With Bonham slowing down the tempo even further on “Fool in the Rain,” albums like In Through the Out Door showed listeners what Zeppelin could achieve with synthesizers even after their heyday.

Even though it was met with mixed reviews at the time, “D’yer Ma’ker” conveys a far stronger message than Zeppelin’s lack of effort. Zeppelin was never going to be a one-trick pony, and they didn’t mind trying new things, even if they ended up being a huge failure.